CHANGING THE FACES OF FASHION THROUGH COMMUNITY: AN INTERVIEW WITH CARLOS CASTELLANOS

Share

Fashion is an industry of constant change—ideas that flow rapidly, trends and aesthetics that dominate for certain periods and then fade away… It would seem that this is an industry also accustomed to change. Except when it comes to the ideals and narratives around beauty that it has built and maintained for decades.

Encouraging change in an industry so steadfast in upholding an ideal—sometimes a harmful one—is complicated. And it’s not something that can be done alone.

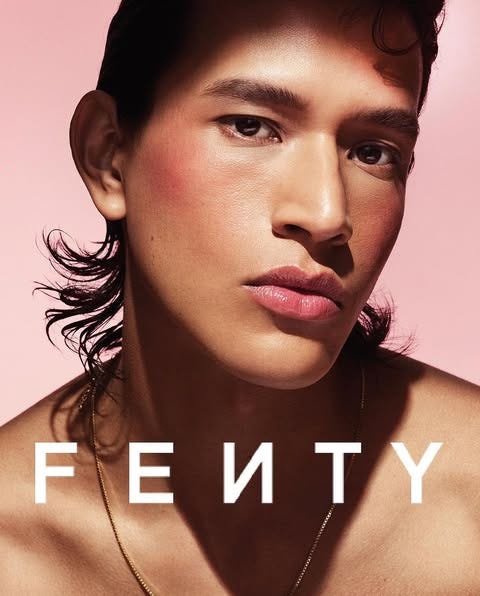

For the first edition of Faces Changing the Industry, Bazar by Hotbook spoke with Carlos Castellanos, creative founder of In The Park Management, the creative home of a community that seeks to bring forward the unique beauty of each of the talents it represents.

Through this work, Carlos, his team, and the talent they have nurtured have introduced faces that resonate beyond the fashion industry and propose reinventing the notion of beauty to claim a space that is not just diverse but real.

Bazar by Hotbook: You’ve inhabited multiple spaces within the fashion industry, likely witnessing firsthand its mistakes (and horrors), moving through eras where diversity was considered “not marketable” and now something even desirable—perhaps even profitable. In this sense, what do you think genuine incorporation of diversity in fashion would look like?

Carlos Castellanos: I believe one of the main issues when brands approach diversity is the lack of follow-through. It doesn’t feel genuine.

Often, they choose models with certain skin tones or gender expressions based on the concept of a collection. We’ve seen this in cases like Carolina Herrera or Dior, where they come to Mexico, get “inspired” or even take from its culture, praise its beauty and its people—yet once they leave, they no longer consider these talents for global projects. What are they truly contributing? It seems as though they are simply fulfilling a quota to justify using certain resources—and, well, to ease their guilt.

The genuine incorporation of diversity in fashion also needs to address the economic dimension. It’s evident that many models are paid less simply because they don’t have established careers. When brands look for fresh faces, they usually pay them less—especially if they are from Mexico or have gender expressions outside the hegemonic norm. Additionally, many of these individuals are far from the fashion capitals, making their visibility even more challenging. The lack of ongoing support from brands prevents these models from being equitably considered in economic terms.

The most consolidated modeling careers still adhere to a hegemony. They follow predictable trajectories with clear strategies to take a model from point A to point B. However, when it comes to people with non-hegemonic features or who don’t fit traditional beauty standards, the question remains: Who is truly investing in them? Who is supporting them?

On the other hand, genuine diversity should not only be reflected in model selection but also in work teams—design, production, creative direction. Sensitivity is not enough; it is essential that these individuals belong to the groups they seek to represent. In many projects I’ve been part of, the teams don’t understand the culture of the communities they are trying to include, nor the issues they face. This is especially evident when it comes to gender expression: many brands see it solely as a marketing strategy, but they lack knowledgeable individuals on their teams to address these topics with the depth and respect they require.

And I believe diversity should be a true reflection of those within the internal team.

BbH: Following this train of thought, how has In The Park navigated an industry with so many underlying economic interests and power positions still reserved for certain people? Specifically, what role has creating a community and surrounding yourself with like-minded individuals played in this journey?

CC: As a director, I have gone through a process of deconstruction, shedding many racist and classist beliefs and prejudices. This has allowed me to understand how the system operates—a system that, ultimately, is solely focused on selling and making the rich even richer. When I grasped the power of representation and the role we play as audiovisual content creators, I connected deeply with this fight.

Even though I come from a hegemonic identity—I am a white man, considered gay, and in many ways more accepted—I have experienced rejection and a lack of understanding toward my desires and artistic work. That’s where my need to guide, nurture, and create an environment of understanding and connection between my office and the models or artists we work with comes from.

Our first role is acknowledging that there is a real struggle. We must knock on many doors and develop strategies to get brands and projects to believe in the people we represent.

On one hand, our impact has been internal: we’ve built In The Park as both a company and a community. Here, support is mutual—there is a constant exchange between us and them, which strengthens their confidence, faith, and hope. Among models and artists, we create a space of connection and resilience.

On the other hand, our strongest role as a company has been the fight for fair conditions. From the start, we established a dialogue about treatment and hiring conditions. In Mexico, formality in this field has been scarce, and while there has been progress, there have also been setbacks. It’s a push-and-pull process. However, I can acknowledge that some clients in Mexico have begun to understand the seriousness of representation and the importance of hiring fairly. It’s not just about playing with someone’s dream of being there.

I don’t see myself as a savior, nor do I want to romanticize it. We’re simply doing our job the way we believe it should be done—and that means having a lot of uncomfortable conversations with the system.

We have had to speak up in multiple projects, questioning practices and highlighting problems. Mexico should be much more than the background or the landscape of many foreign productions, they should consider their people. We remain a country that is sought after for its competitive prices, but in terms of artistic and human appreciation, there is still much to challenge. I don’t want to generalize, but in many cases, the industry still operates this way—superficially…

As for surrounding myself with like-minded individuals, I think it’s key. The people around me fully understand the importance of maintaining dialogue and mutual support. It’s beautiful to see how models recommend each other, or how, now that we represent actors and actresses, they also support one another in different projects. It’s about breaking down egos and fostering a community where support is genuine.

BbH: You have previously mentioned that the fantasy presented by magazine covers and pages does not reflect our reality and is a false representation of "human perfection." However, the fashion industry seems insistent on the narrative of fashion as a "fantasy" or aspiration rather than something that should reflect reality. Do you think fashion should be a dream? Is it possible for fashion to dream with people who share our features?

CC: It’s complex. There’s no single way to represent diversity—it’s too vast to box in, especially in a globalized world where power players dictate how fashion “should” look.

But yes, fashion is a fantasy. It creates illusions of progress, advancement, and behavior. The problem is we ask too few questions or let algorithms dictate us.

So, should fashion be a dream? Yes. It’s a tool to spark questions and desires—desires that should benefit everyone. But commercial and elite interests often oppose progress.

Efforts for representation can be made. But let’s talk about In The Park. Some might view our portfolio and say, “They are missing a girl with vitiligo, a wheelchair user, more Afro-Mexicans…?” Yes, we’re missing much. It’s been tough because we operate within an established economic ecosystem.

I can’t just open an agency and say, “Welcome, all!” without process. Imagine shooting someone beautifully [and starting to get booked], but what happens next? I don’t want them to become objects for foreign photographers to exploit unpaid—a rampant issue.

At In The Park, we avoid tokenism—we’re not a “hyperdiverse” website facade without real opportunities. It’s about choosing battles: representing someone means entering their life and existence sincerely.

I wouldn’t call us Mexico’s most diverse agency, but we genuinely aspire to be. Some models fit industry “standards,” yet push boundaries. But we still face industry limits. Sometimes you see someone and think, “They could break through,” but it takes years… or never happens. We constantly ask how models navigate this emotionally.

We know the industry has far to go. Accepting slow progress is part of the process. Pre-pandemic, curvy models and Indigenous communities gained visibility, but it’s receded. It was a performance—marketing to sell “uniqueness.”

BbH: Your work challenges Eurocentrism and the cis-hetero norm. What’s your experience positioning In The Park as an agency embracing intersectional diversity?

CC: Starting the agency was organic. It began with a question: What happens to Mexican models? Why are they invisible globally? Sure, they existed, but in the social consciousness there were only the three girls embodying the ideal white Mexican women.

Gender fluidity emerged naturally too. When Magdaleno Delgado told me, “I’m non-binary,” I was uneducated. they taught me. Their career began non-binary, but agencies abroad pushed a neutral, jeans-and-T-shirt look to fit in. They broke norms, appearing on Models.com’s male and female lists—a thrilling moment. Interviews poured in.

But when they said, “I want to wear heels,” we hit walls. Fashion remains deeply binary. This system affects female presenting models too, although in different ways. Few female presenting models are allowed to express their femininity and are asked to present an agender version of themselves, even physically.

Few brands embrace gender fluidity, and paradoxically, those that do lack resources to invest in diverse models. Bridging brands, creatives, and artists who value diversity is crucial for sustainability.

Positioning the agency has been tough. Brands open to diversity often lack funds for international careers. How do we build careers in diversity when industry structures remain binary?

As a director, I face hard choices. If a femme-expressing model has a masc physique by industry standards, how do we place them in womenswear without compromising identity? It’s a balance between respecting identity and navigating existing—and only paying—spaces.

BbH: In The Park’s personalized approach to talent—exploring desires and expressions—has let thousands see themselves in faces like Trini, Magda, Sara… Was this always the focus, or a learned process? And what’s the power of representation in fashion/entertainment?

CC: Personalization was a response to modeling’s dehumanization. Global agencies invest little in dialogue or listening. The industry’s anxiety-driven pace chases “the new” without questioning what happens to people.

It often operates on convenience: “If they’re easy, incredible, functional—invest time. If not, discard.” For me, personalization is resistance. Careers here take years, with ups and pauses. But we believe every person has something to represent.

Representation’s power has driven our success. Many join In The Park because they see themselves here.

In fashion/entertainment, representation’s impact is huge. These fields shape aspirations and identities, yet have long excluded many.

We live in a world craving community, yet fashion/entertainment alienate, perpetuating a vicious power cycle. We’re taught to aspire to figures we don’t resemble—feeding systemic profit. If you spend life wanting to look like Brad Pitt (why him?), the system sells the illusion that surgeries or products might get you closer. It thrives on dissatisfaction.

Hearing our talents’ stories matters. We see ourselves in their journeys and think, “Hell yes, I can too.”

The big question I always hold: Who is still benefiting from all this?

BbH: A thread in your work is urging us to not just see Mexican beauty but see ourselves as beautiful—to reject harmful, historical narratives. So, what makes someone beautiful, model or not?

CC: It’s tough. For me, beauty is someone who loves. But to love, one must first be loved.

Beauty lies in humor, respect, empathy, solidarity, honesty. These values define it—not needing all, but they matter.

Our obsession with faces and bodies is a distraction. Physically, beauty is subjective.

There’s beauty in everything and everyone.

Dismantling narrow ideals of beauty is the hardest work.

Carlos Castellanos and In The Park Management exemplify the urgent need for fashion to move beyond performative diversity and confront its systemic inequities head-on.

By prioritizing community, economic justice, and intersectional representation, their work challenges the industry to replace hollow gestures with sustained, meaningful action.

While the road to dismantling beauty standards and power structures remains long, their approach—rooted in empathy, dialogue, and authenticity—proves that real change is possible when creativity and ethics align. The dream of a truly inclusive fashion landscape isn’t a distant fantasy; it’s a collective project, one that demands reimagining beauty as a celebration of humanity in all its forms.